Growing the language: adding let 扩展语言:添加 let

Every time we enhance our source language, we need to consider several things:

每次我们增强源语言时,都需要考虑以下几点:

- Its impact on the concrete syntax of the language 对语言具体语法的影响

- Examples using the new enhancements, so we build intuition of them 使用新增强功能的示例,以便我们建立对这些功能的直观理解

- Its impact on the abstract syntax and semantics of the language

对语言抽象语法和语义的影响 - Any new or changed transformations needed to process the new forms

处理新形式所需的新增或变更转换 - Executable tests to confirm the enhancement works as intended

用于确认增强功能按预期工作的可执行测试

The new syntax, both concrete and abstract 新的语法,包括具体和抽象

Let’s grow the language above further, by adding the concepts of identifiers and let-bindings:

让我们通过添加标识符和 let 绑定的概念,进一步扩展语言功能:

‹prog›: def main ( IDENTIFIER ) : ‹expr›

‹expr›:

| NUMBER

| add1 ( ‹expr› )

| sub1 ( ‹expr› )

| IDENTIFIER

| let IDENTIFIER = ‹expr› in ‹expr›

We’ve changed a few things syntactically:

我们在语法上做了一些改变:

-

We allow the argument to the

mainfunction to be any identifier, rather than hard-coding the choice ofx

我们允许main函数的参数可以是任何标识符,而不是硬编码x的选择 -

Similarly, we allow variables used to be any identifier.

类似地,我们允许使用的变量可以是任何标识符。 -

We add a

letexpression,let x = e1 in e2

我们添加了一个let表达式,let x = e1 in e2

This change means we now need abstract syntax for programs and expressions, which we update as follows:

这个改变意味着我们现在需要程序和表达式的抽象语法,我们按如下方式更新:

type Var = String;

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub struct Program {

pub parameter: Var,

pub body: Expression,

}

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub enum Expression {

Variable(Var),

Number(i64),

Add1(Box<Expression>),

Sub1(Box<Expression>),

Let(Var, Box<Expression>, Box<Expression>),

}

This time we add an abstract syntax form for Programs since we now allow for an arbitrary variable name used in the parameter.

这次我们为 Program 添加了抽象语法形式,因为我们现在允许在参数中使用任意变量名。

Examples and Well-formedness Conditions 示例和良好形成条件

Let’s start by taking a look at a few example programs that match this grammar. If we write the let form sequentially, this looks much like C-style imperative programming.

让我们先看看几个符合这种语法的示例程序。如果我们按顺序编写 let 形式,这看起来很像 C 风格的命令式编程。

def main(x):

let y = sub1(x) in

let z = add1(add1(y)) in

add1(z)

But notice that let is allowed in expression position so we get some perhaps unexpected combinations:

但请注意, let 被允许在表达式位置,所以我们得到一些可能不太意外的组合:

def main(x):

let z =

let y = sub1(x) in

add1(add1(y)) in

add1(z)

or even 或者甚至

def main(x):

let z = add1(add1(let y = sub1(x) in y)) in

add1(z)

In C-like languages variable binding is included in statements which are a separate syntactic class from expressions. Statements do something which has a side-effect, and can contain expressions, which evaluate to some result. In the Snake language, instead we follow the style of functional programming languages, where we dispense with this distinction and make all constructs into expression constructors. This makes the language a bit more uniform, and as we’ll see when we get further into compilation, functional and imperative languages are ultimately not all that different when viewed from the perspective of the compiler.

在类似 C 的语言中,变量绑定包含在语句中,而语句是一个与表达式不同的语法类别。语句执行具有副作用的操作,并且可以包含表达式,这些表达式会求值得到某个结果。在 Snake 语言中,我们遵循函数式编程语言的风格,摒弃这种区别,将所有构造都变成表达式构造器。这使得语言更加统一,正如我们在深入编译过程时会看到的,从编译器的角度来看,函数式语言和命令式语言最终并没有太大区别。

Rust in particular takes a sort of middle ground in the statement vs expression divide, owing to its functional roots. In Rust, a let is a statement, but statements themselves can produce a value, more similar to expression forms. So the Rust equivalent of our unusual example above would be

Rust 在声明与表达式之间的分界上采取了某种中间立场,这得益于其函数式编程的根源。在 Rust 中,一个声明 let 是一个声明,但声明本身可以产生一个值,这更类似于表达式形式。因此,我们上面那个不寻常的例子在 Rust 中的等价形式是

fn add1(x: i64) -> i64 {

x + 1

}

fn sub1(x: i64) -> i64 {

x - 1

}

fn funny(x: i64) -> i64 {

let z = {

add1(add1({

let y = sub1(x);

y

}))

};

add1(z)

}

Another thing we should notice about our syntax is that unlike our previous languages, there are some well-formed terms in our concrete syntax that don’t look like well-formed programs. For example the program

关于我们的语法,我们还需要注意的一点是,与之前的语言不同,在我们的具体语法中,有一些结构良好的术语看起来并不像结构良好的程序。例如,程序

def main(x):

y

Do Now! 现在动手!

Should this program be accepted by our language? Why or why not?

我们的语言应该接受这个程序吗?为什么或者为什么不?

Semantic Analysis and Scope 语义分析和作用域

Most programming languages will reject such a program at compile-time, the reason being that the variable y has not yet been declared. This is an example where the abstract syntax tree doesn’t fully capture all of the invariants that the programs in our language need to satisfy. This is typical in programming languages: even after parsing into a syntax tree, there are more sophisticated properties like variable usage, type checking, borrow checking etc. that are performed. This phase of the compiler after parsing is sometimes called semantic analysis, as opposed to the simple syntactic analysis performed by the parser. The combination of lexing, parsing and semantic analysis are collectively called the frontend of the compiler. We can identify when we’ve reached the end of the frontend of the compiler when we are able to define a semantics.

大多数编程语言会在编译时拒绝这样的程序,原因在于变量 y 尚未声明。这是一个抽象语法树未能完全捕捉到我们语言中程序所需满足的所有不变式的例子。这在编程语言中很常见:即使解析成语法树后,仍然会进行更复杂的属性检查,如变量使用、类型检查、借用检查等。编译器在解析之后的这个阶段有时被称为语义分析,与解析器执行的简单语法分析相对。词法分析、解析和语义分析的组合统称为编译器的前端。当我们能够定义语义时,就表明我们已经到达了编译器前端的结束。

Let’s set some terminology. We reject the program above because the usage of y happens in a context in which y is not in scope. We call such a y a free variable. On the other hand, in the similar program

让我们设定一些术语。我们拒绝上述程序,因为 y 的使用发生在 y 不在作用域的上下文中。我们将这种 y 称为自由变量。另一方面,在类似的程序中

def main(x):

x

There are two occurrences of x. The first one is as a parameter to the main function. We call this the binding-site for x, and the second the usage of x. In this usage, x is a bound variable, or that it is in the scope of its binding site.

这里有两次出现 x 。第一次是作为 main 函数的参数。我们称这个为 x 的绑定位置,第二次是 x 的使用。在这种使用中, x 是一个绑定变量,或者说它在它的绑定位置的作用域内。

Do Now! 现在动手!

Identify the binding sites, free variables and bound variables in the following term:

识别下列项中的绑定位置、自由变量和绑定变量:

def main(x): let y = let z = x in add1(y) in let w = sub1(x) in sub1(z)

In this program, there are 4 binding sites: def main(x), let y = , let z = and let w =. There are 4 occurrences of variables, x in let z = x in add1(y), y in add1(y), x again in sub1(x) and z in sub1(z). Of these, the occurrences of x are bound, referencing the parameter of the main function, but the occurrences of y and z are free. The occurrence of y is unbound because the scope of y in let y = e1 in e2 is only e2, not e1. Similarly, while there is a declaration of z, the use of z is not in a sub-tree of that let z at all, and so similarly it is a free variable.

在这个程序中,有 4 个绑定位置: def main(x) 、 let y = 、 let z = 和 let w = 。有 4 次变量出现,分别是 x 在 let z = x in add1(y) 中、 y 在 add1(y) 中、 x 再次在 sub1(x) 中以及 z 在 sub1(z) 中。其中, x 的出现是绑定的,它引用了 main 函数的参数,但 y 和 z 的出现是自由的。 y 的出现是无绑定的,因为 y 在 let y = e1 in e2 中的作用域仅限于 e2 ,而不是 e1 。类似地,虽然存在 z 的声明,但 z 的使用完全不在 let z 的子树中,因此它也是一个自由变量。

We can formalize this property in code, by writing a function

我们可以在代码中形式化这个属性,通过编写一个函数

check_scope(&Program) -> Result<(), ScopeError>

In the design of such a function, we again apply our strategy of programming with expressions by recursive descent. To do so, we realize that we need some auxiliary data to keep track of which variables are currently in scope. In this case, we can use a set of variables that are currently in scope. We call an auxiliary data structure like this that keeps track of which variables are in scope an environment.

在这样一个函数的设计中,我们再次应用通过递归下降进行表达式编程的策略。为此,我们意识到我们需要一些辅助数据来跟踪当前在作用域内的变量。在这种情况下,我们可以使用一组当前在作用域内的变量。我们将这种跟踪哪些变量在作用域内的辅助数据结构称为环境。

Semantics 语义

Do Now! 现在动手!

Extend the interpreter from last time to handle the new constructs in this language. You will need a function with signature

扩展上次介绍的解释器,以处理这种语言中的新结构。您需要一个具有以下签名的函数

interpret(&Program, i64) -> i64...and you will certainly need a helper function. What should that function do, and what should its signature be?

...并且您当然需要一个辅助函数。这个函数应该做什么,它的签名应该是什么?

Writing this interpreter is straightforward, at least initially: numbers evaluate to themselves, and adding or subtracting one from an expression should simply evaluate the expression and then add or subtract one from the result. But what should we do about identifiers and let-bindings?

编写这个解释器至少在初始阶段是直接的:数字求值为自己,从表达式中加上或减去一个数应该简单地求值表达式,然后从结果中加上或减去一个数。但我们应该如何处理标识符和 let 绑定呢?

We first need to make a choice in our semantics, how does an expression let x = e1 in e2 evaluate. The two simplest choices are:

我们首先需要在语义上做出选择,表达式 let x = e1 in e2 如何求值。最简单的两种选择是:

-

We evaluate

e1down to a numbern, and then proceed to evaluatee2, remembering thatxnow corresponds ton

我们将e1求值到数字n,然后继续求值e2,记住x现在对应n -

We immediately proceed to evaluate

e2, but remembering thatxnow corresponds to the expressione1

我们立即求值e2,但记住x现在对应表达式e1

The first strategy is called eager evaluation and is the most common in programming languages. The latter strategy is called lazy evaluation, and is used in some functional languages, most famously Haskell. To implement eager or lazy evaluation in our interpreter, we will have to keep track of a new kind of environment. This time the environment will not be simply a set of variables that are in scope, but a mapping from variable names to their associated meaning. The meaning of the variables is what differs in the two different evaluation strategies:

第一种策略称为急求值,是编程语言中最常见的。后一种策略称为惰求值,在一些函数式语言中使用,最著名的是 Haskell。为了在我们的解释器中实现急求值或惰求值,我们将不得不跟踪一种新的环境。这次环境将不仅仅是作用域内的变量集合,而是一个从变量名到其相关含义的映射。变量的含义是两种不同求值策略之间的区别:

-

In lazy evaluation, we need an environment that maps variables to expressions, and only run the expression when the variable is used.

在惰性求值中,我们需要一个将变量映射到表达式的环境,并且只在变量被使用时才运行该表达式。 -

In eager evaluation, we need an environemnt that maps variables to values, in our case integers, so using a variable is just a lookup in the environment.

在急速求值中,我们需要一个将变量映射到值的环境,在我们的情况下是整数,因此使用变量只是一个在环境中查找的过程。

Do Now! 现在动手!

Suppose we added an infix

Plus(Box<Exp>, Box<Exp>)operation. Construct a program whose running time is drastically worse with the first environment type, compared to the second environment type.假设我们添加了一个中缀

Plus(Box<Exp>, Box<Exp>)操作。构建一个程序,使其在第一种环境类型下的运行时间与第二种环境类型相比要差得多。Suppose we added an expression

Print(Box<Exp>)that both prints its argument to the console, and evaluates to the same value as its argument. Construct a program whose behavior is actually different with the two environment types.假设我们添加了一个表达式

Print(Box<Exp>),它既将参数打印到控制台,又与参数具有相同的求值结果。构建一个在两种环境类型下行为不同的程序。

Shadowing 遮蔽

There is one final subtlety to variable names to address. Consider the following expression

还有一个关于变量名的微妙之处需要处理。考虑以下表达式

let x = 1 in

let x = 2 in

x

Should we accept or reject this program? Most programming languages, for example Rust, will accept it, and its value will be 2. This phenomenon, where an inner variable binding overrides an outer one is called shadowing, we say that the second binding site shadows the first one. An unusual consequence of allowing shadowing is that if a variable is shadowed it cannot be directly accessed inside the shadowing binding, as the name is now being used for something else.

我们应该接受还是拒绝这个程序?大多数编程语言,例如 Rust,会接受它,其值将是 2 。这种现象,即内部变量绑定覆盖外部绑定,称为遮蔽,我们称第二个绑定位置遮蔽了第一个。允许遮蔽的一个不寻常的后果是,如果变量被遮蔽,则不能在遮蔽绑定内部直接访问它,因为该名称现在被用于其他用途。

Allowing shadowing is convenient and intuitive to programmers, but raises some implementation pitfalls we should be aware of. Consider the task of optimizing the input program. Say we are working with an expression let x = e1 in e2 where e1 is a fairly simple term like a number or a variable or just one add1, then we could simplify the term by simply replacing all occurrences of x in e2 with e1.

允许遮蔽对程序员来说很方便且直观,但会引发一些我们应当注意的实现陷阱。考虑优化输入程序的任务。假设我们正在处理一个表达式 let x = e1 in e2 ,其中 e1 是一个相当简单的项,比如一个数字或一个变量,或者只是一个 add1 ,那么我们可以通过简单地用 e1 替换 e2 中所有出现的 x 来简化这个项。

For instance the expression

例如表达式

let x = y in

let z = add1(x) in

add1(add1(z))

can be simplified to

可以简化为

let z = add1(y) in

add1(add1(z))

This simplification is called beta reduction, and when done in reverse is called common subexpression elimination. Both beta reduction and common subexpression elimination can speed up programs depending on the complexity of recomputing e1 and how x is used in the program.

这种简化称为β还原,反向进行时称为公共子表达式消除。β还原和公共子表达式消除都可以根据重新计算 e1 的复杂性和 x 在程序中的使用方式来加速程序。

This looks like a fairly benign operation, but if we’re not careful, we can unintentionally change the behavior of the program!

这看起来像是一个相当无害的操作,但如果不小心,我们可能会无意中改变程序的行为!

Do Now! 现在动手!

Can you give an example program in which the textual substitution of

e1forxine2differs in behavior fromlet x = e1 in e2? Hint: it will involve shadowing你能给出一个示例程序,其中在

e2中将e1替换为x的行为与let x = e1 in e2不同吗?提示:这将涉及遮蔽

def main(y):

let x = y in

let y = 17 in

add1(x)

This program implements a function that adds 1 to the input. If we naively replace all occurrences of x with y, we end up with

这个程序实现了一个函数,将 1 加到输入上。如果我们天真地替换所有 x 为 y ,我们会得到

def main(y):

let y = 17 in

add1(y)

which always returns 18! The reason is that the meaning of a variable y is dependent on the environment, and in this case there are two different binding sites that bind the variable y. In fact, because of shadowing it is impossible to refer to the outer definition of y in the body of let y = 17. How can we solve this issue? We notice that this is really only a problem with the fact that the names happen to be the same, but the actual String name of the variable is not really relevant to execution, the only purpose of the name is to identify which binding site the variable refers to. If we were to consistently change the names at the binding sites along with their corresponding uses, we would produce an equivalent program. A simple way to do this is to append a unique number to all identifiers, so that we can still recall the original names for better error messages and more readable intermediate code when debugging, but to ensure that all binding sites have unique names so that we cannot accidentally conflate them. After such a name resolution pass the program would look like

它总是返回 18 !原因在于变量的意义依赖于环境,而在这个情况下,有两个不同的绑定位置绑定变量 y 。实际上,由于遮蔽效应,在 let y = 17 的体内不可能引用 y 的外部定义。我们该如何解决这个问题?我们注意到,这确实只是一个问题,即名称碰巧相同,但变量的实际 String 名称与执行无关,名称的唯一目的是识别变量引用哪个绑定位置。如果我们能够始终如一地更改绑定位置及其相应使用的名称,我们将生成一个等效的程序。一种简单的方法是将唯一编号附加到所有标识符上,这样我们仍然可以回忆起原始名称,以便在调试时提供更好的错误消息和更易读的中间代码,但确保所有绑定位置都有唯一的名称,以防止我们意外混淆它们。经过这样的名称解析过程后,程序将看起来像

def main(y#0):

let x#0 = y#0 in

let y#1 = 17 in

add1(x#0)

And applying the naive substitution now preserves the intended meaning of the variable names:

并且现在应用简单的替换可以保持变量名的预期含义:

def main(y#0):

let y#1 = 17 in

add1(y#0)

For this reason, it is common in compilers to perform a renaming pass that ensures that all binding sites have globally unique names, and to maintain this invariant for the remainder of the compilation process.

因此,在编译器中,通常会执行一个重命名阶段,以确保所有绑定位置都具有全局唯一的名称,并在编译过程的其余部分保持这一不变性。

Exercise 练习

Implement a function resolve_names(p: &Program) -> Program that renames all variables to unique identifiers. As before, you will need to carry some kind of environment. What data structure is appropriate for the environment in this case?

实现一个函数 resolve_names(p: &Program) -> Program,将所有变量重命名为唯一标识符。和之前一样,你需要维护某种类型的环境。在这种情况下,哪种数据结构适合用于环境?

Compiling Variables and Let-expressions 编译变量和 Let 表达式

When we turn to the task of compiling our expressions, we see that the presence of a context of variables complicates matters. Previously, we stored all intermediate results in rax, and our two base cases of a number and usage of the single input variable would mov a constant, or the value of rdi into rax, respectively. We were able to use rdi before because we knew there was only a single variable, but now there are arbitrarily many different variables, and so we need to store each of their corresponding values in distinct memory locations. That is, just as how in the scope checker we needed an environment to know which variables were in scope, and in the interpreter we needed an environment to know what values the in-scope variables had, for the compiler we also need an environment, which tells us where the variables’ values are stored.

当我们转向编译表达式的任务时,我们发现变量上下文的存在使问题变得复杂。之前,我们将所有中间结果存储在 rax 中,而数字和单个输入变量使用这两种基本情况会 mov 一个常量,或者将 rdi 的值赋给 rax 。我们之前能够使用 rdi ,是因为我们知道只有一个变量,但现在有任意多个不同的变量,因此我们需要将它们各自对应的值存储在不同的内存位置。也就是说,就像在作用域检查器中我们需要环境来知道哪些变量在作用域内,在解释器中我们需要环境来知道作用域内变量的值是什么一样,对于编译器我们也需要环境,它告诉我们变量的值存储在哪里。

x86: Addressable Memory, the Stack x86:可寻址内存,栈

So far our only access to memory in x86-64 has been the registers. But there are only 16 of these, giving us only 128 bytes of memory to work with. Since each variable in our source language holds an 64-bit integer, and we can have arbitrarily many variables, we need access to more memory than just the registers. In the x86-64 abstract machine, in addition to the registers, we also have access to byte-addressable memory, where addresses are themselves 64-bit integers. So this would seem to imply that we have access to 2^64 bytes of memory, though in reality current hardware only considers the lower 48 bits significant. Still this gives us access to 256 terabytes of addressable memory, which should be plenty for our applications.

到目前为止,我们在 x86-64 架构中唯一可以访问的内存是寄存器。但只有 16 个寄存器,这给我们提供的内存只有 128 字节。由于我们源语言中的每个变量都存储一个 64 位整数,并且我们可以有任意数量的变量,我们需要访问比寄存器更多的内存。在 x86-64 抽象机中,除了寄存器之外,我们还可以访问字节寻址的内存,其中地址本身也是 64 位整数。因此,这似乎意味着我们可以访问 2^64 字节的内存,尽管实际上当前硬件只认为低 48 位是有效的。尽管如此,这也让我们可以访问 256TB 的可寻址内存,这对我们的应用来说应该足够了。

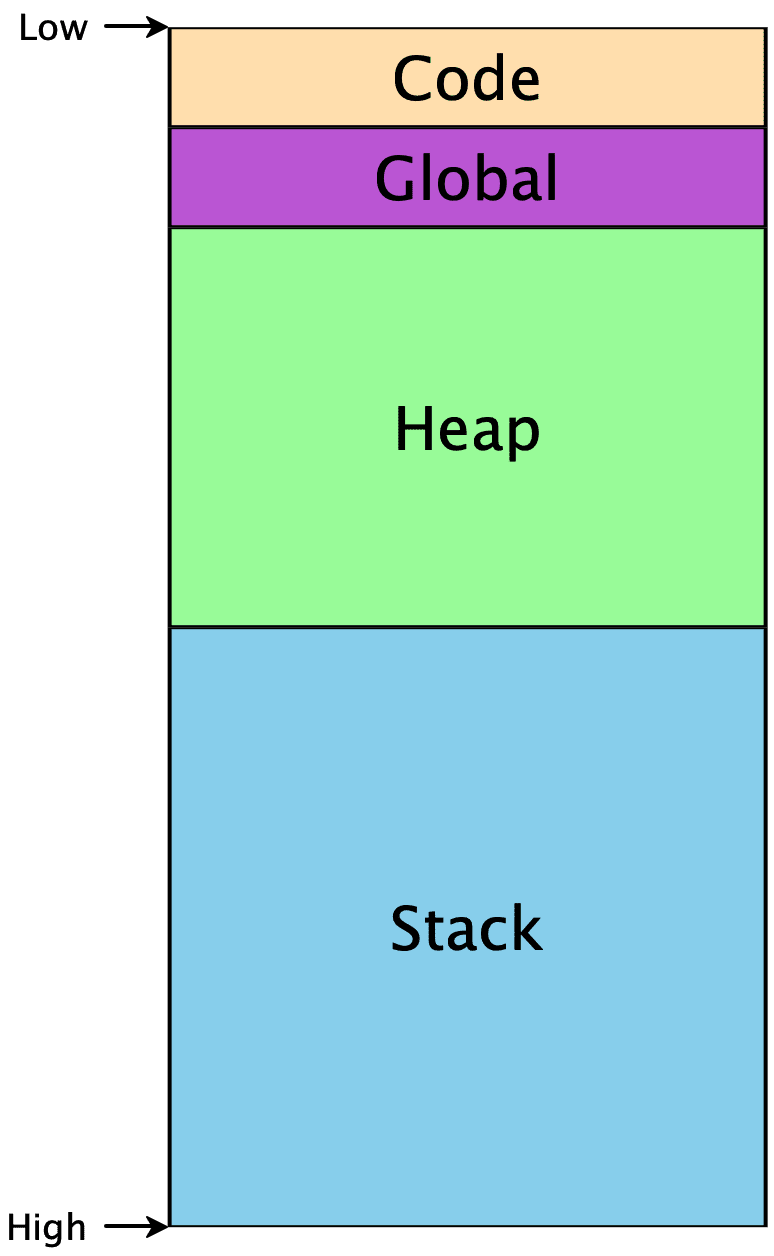

Programs don’t start at memory address 0, or at address 264, but they do have access to some contiguous region:

程序并非从内存地址 0 或地址 264 开始,但它们确实可以访问某个连续的区域:

The Code segment includes the code for our program. The Global segment includes any global data that should be available throughout our program’s execution. The Heap includes memory that is dynamically allocated as our program runs — we’ll come back to using the heap later. Finally the Stack segment is used as our program calls functions and returns from them — we’ll need to work with this segment right away.

代码段包含我们程序的代码。全局段包含任何应在我们的程序执行期间可用的全局数据。堆包含在程序运行时动态分配的内存——我们稍后会回到使用堆。最后,栈段用于我们的程序调用函数并从它们返回——我们需要立即与这个段合作。

Because the heap and the stack segments are adjacent to each other, care must be taken to ensure they don’t actually overlap each other, or else the same region of memory would not have a unique interpretation, and our program would crash. This implies that as we start using addresses within each region, one convenient way to ensure such a separation is to choose addresses from opposite ends. Historically, the convention has been that the heap grows upwards from lower addresses, while the stack grows downward from higher addresses.1This makes allocating and using arrays particularly easy, as the ith element will simply be i words away from the starting address of the array.

由于堆和栈段是相邻的,必须小心确保它们不会实际重叠,否则同一内存区域将不会有唯一的解释,并且我们的程序会崩溃。这意味着当我们开始使用每个区域内的地址时,一种确保这种分离的方便方法是从两端选择地址。从历史上看,惯例是堆从较低的地址向上增长,而栈从较高的地址向下增长。

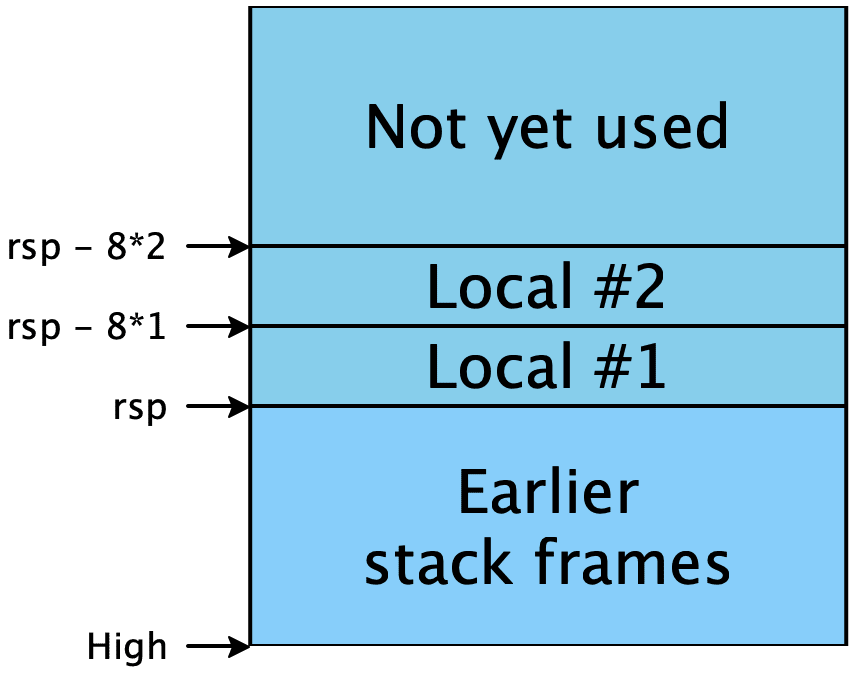

The stack itself must conform to a particular structure, so that functions can call each other reliably. This is (part of) what’s known as the calling convention, and we’ll add more details to this later. For now, the high-level picture is that the stack is divided into stack frames, one per function-in-progress, that each stack frame can be used freely by its function, and that when the function returns, its stack frame is freed for use by future calls. (Hence the appropriateness of the name “stack”: stack frames obey a last-in-first-out discipline as functions call one another and return.) When a function is called, it needs to be told where its stack frame begins. Per the calling convention, this address is stored in the rsp register (read sp as standing for “stack pointer”)2This is a simplification. We’ll see the fuller rules soon.. Addresses lower than rsp are free for use; addresses greater than rsp are already used and should not be tampered with:

栈本身必须遵循特定的结构,以便函数能够可靠地相互调用。这就是所谓的调用约定(的一部分),我们稍后会对此添加更多细节。目前,高层次的概念是栈被划分为栈帧,每个正在执行的函数都有一个栈帧,每个栈帧都可以被其函数自由使用,当函数返回时,其栈帧会被释放以供未来的调用使用。(因此“栈”这个名字的恰当性:当函数相互调用并返回时,栈帧遵循后进先出的原则。)当函数被调用时,需要被告知其栈帧的起始位置。根据调用约定,这个地址存储在 rsp 寄存器中(将 sp 理解为“栈指针”)。低于 rsp 的地址可供使用;高于 rsp 的地址已经被使用,不应被篡改:

To access memory in x86, we need to "dereference" an address, syntactically, this is written by surrounding the address in square brackets. For instance to move a value from rdi to rax, we write mov rax, rdi, but to load a value from the memory pointed to by rdi we write mov rax, [rdi]. Vice-versa, to store the value in the register rdi in the memory pointed to by rax, we write mov [rax], rdi. Most instructions in x86 that work with registers work just as well with addresses, with the exception that there can only be one memory access in the instruction. So for instance, we cannot write mov [rax], [rdi], we would instead need to first load [rdi] into a register and then store it to [rax].

要在 x86 中访问内存,我们需要“解引用”一个地址,在语法上,这是通过将地址用方括号括起来来表示的。例如,要从 rdi 移动值到 rax ,我们写 mov rax, rdi ,但要加载由 rdi 指向的内存中的值,我们写 mov rax, [rdi] 。反过来,要将寄存器 rdi 中的值存储到由 rax 指向的内存中,我们写 mov [rax], rdi 。x86 中大多数与寄存器工作的指令同样适用于地址,唯一的例外是这条指令中只能有一个内存访问。所以例如,我们不能写 mov [rax], [rdi] ,我们需要先将要加载的 [rdi] 到寄存器中,然后再存储到 [rax] 。

Mapping Variables to Memory 将变量映射到内存

The description above lets us refine our compilation challenge: we have a large region of of memory available to us on the stack, and we can store our variables at locations rsp - 8 * 1, rsp - 8 * 2, ... rsp - 8 * i.

上述描述让我们能够细化我们的编译挑战:我们可以在栈上获得一大片内存区域,并且可以将我们的变量存储在 rsp - 8 * 1 、 rsp - 8 * 2 、 ... rsp - 8 * i 等位置。

Exercise 练习

Why do we use multiples of 8?

为什么我们使用 8 的倍数?

Exercise 练习

Given the description of the stack above, come up with a strategy for allocating numbers to each identifier in the program, such that identifiers that are potentially needed simultaneously are mapped to different numbers.

根据上述栈的描述,构思一种分配策略,为程序中的每个标识符分配数字,使得可能同时需要的标识符映射到不同的数字。

One possibility is simply to give every unique binding its own unique integer. Trivially, if we reserve enough stack space for all bindings, and every binding gets its own stack slot, then no two bindings will conflict with each other and our program will work properly.

一种可能性是简单地给每个唯一的绑定分配一个唯一的整数。显然,如果我们为所有绑定预留足够的栈空间,并且每个绑定都有自己的栈槽位,那么没有任何两个绑定会相互冲突,我们的程序将能正常工作。

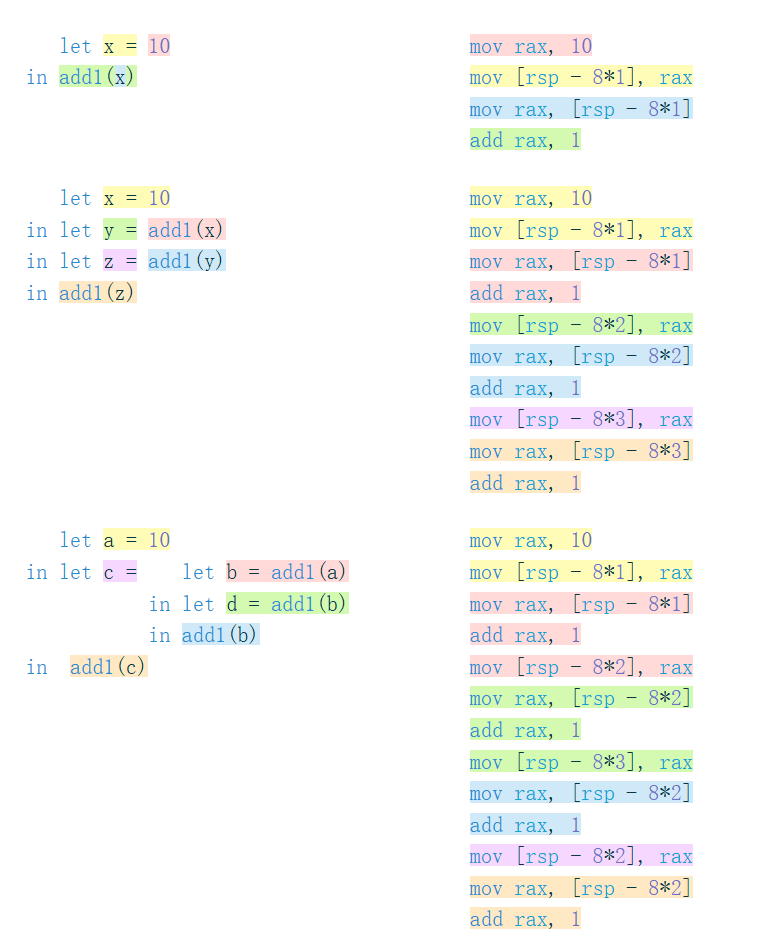

In the following examples, the code is on the left, and the mappings of names to stack slots is on the right.

在以下示例中,代码位于左侧,而名称到栈槽位的映射位于右侧。

let x = 10 /* [] */

in add1(x) /* [ x --> 1 ] */

let x = 10 /* [] */

in let y = add1(x) /* [x --> 1] */

in let z = add1(y) /* [y --> 2, x --> 1] */

in add1(z) /* [z --> 3, y --> 2, x --> 1] */

let a = 10 /* [] */

in let c = let b = add1(a) /* [a --> 1] */

in let d = add1(b) /* [b --> 2, a --> 1] */

in add1(b) /* [d --> 3, b --> 2, a --> 1] */

in add1(c) /* [c --> 4, d --> 3, b --> 2, a --> 1] */

We can implement this strategy fairly easily: we can keep one mutable counter and as we traverse the program, associate each variable with an offset, incrementing the counter to ensure all variables are placed in different locations. However, if we inspect the output of this program carefully, we notice that it doesn’t use the minimal number of stack slots. In the last expression, where we have a left-nested let, the variables b and d have fallen out of scope when we define c. So in fact we don’t actually need to ensure that c uses a different address. Instead, we can re-use the space we used for b to store the value of c.

我们可以相当容易地实现这一策略:我们可以保持一个可变计数器,并在遍历程序时,将每个变量与一个偏移量关联起来,通过递增计数器来确保所有变量都放置在不同的位置。然而,如果我们仔细检查这个程序的输出,我们会发现它没有使用最少数量的栈槽位。在最后一个表达式中,我们有一个左嵌套的 let,当定义 c 时,变量 b 和 d 已经超出了作用域。所以实际上我们并不需要确保 c 使用不同的地址。相反,我们可以重用我们用来存储 b 值的地址来存储 c 的值。

A closer reading of the code reveals that our usage of let bindings also forms a stack discipline: as we enter the bodies of let-expressions, only the bindings of those particular let-expressions are in scope; everything else is unavailable. And since we can trace a straight-line path from any given let-body out through its parents to the outermost expression of a given program, we only need to maintain uniqueness among the variables on those paths. Here are the same examples as above, with this new strategy:

对代码的仔细阅读表明,我们使用 let 绑定也形成了一种栈规则:当我们进入 let 表达式的体时,只有这些特定 let 表达式的绑定在作用域内;其他所有内容都不可用。而且,由于我们可以从任何给定的 let 体直接追踪到其父级,直到给定程序的 最外层表达式,我们只需要在这些路径上的变量中维护唯一性。以下是上面相同的例子,使用这种新策略:

let x = 10 /* [] */

in add1(x) /* [ x --> 1 ] */

let x = 10 /* [] */

in let y = add1(x) /* [x --> 1] */

in let z = add1(y) /* [y --> 2, x --> 1] */

in add1(z) /* [z --> 3, y --> 2, x --> 1] */

let a = 10 /* [] */

in let c = let b = add1(a) /* [a --> 1] */

in let d = add1(b) /* [b --> 2, a --> 1] */

in add1(b) /* [d --> 3, b --> 2, a --> 1] */

in add1(c) /* [c --> 2, a --> 1] */

Only the last line differs, but it is typical of what this algorithm can achieve. Let’s work through the examples above to see their intended compiled assembly forms.3Note that we do not care at all, right now, about inefficient assembly. There are clearly a lot of wasted instructions that move a value out of rax only to move it right back again. We’ll consider cleaning these up in a later, more general-purpose compiler pass. Each binding is colored in a unique color, and the corresponding assembly is highlighted to match.

只有最后一行不同,但它典型地展示了这个算法所能达到的效果。让我们通过上述示例来查看它们预期的编译汇编形式。每个绑定都使用独特的颜色进行标记,相应的汇编代码也会以高亮显示来匹配。

This algorithm is also not really any harder to implement than the previous one: adding a binding to the environment simply allocates it at a slot equal to the new size of the environment. As we descend into a let-binding, we keep the current environment. As we descend into a let-body, we augment the environment with the new binding. And as we exit a let-expression, we discard the augmented environment — the bindings inside it have now fallen out of scope. This usage of the environment is directly analogous to how the scope checking, interpreter and name resolution.

这个算法实现起来也并不比上一个算法更难:向环境中添加一个绑定只需在等于环境新大小的一个槽位中为其分配空间。当我们深入到一个 let 绑定中时,我们保留当前的环境。当我们深入到一个 let 体中时,我们用新的绑定来扩展环境。当我们退出一个 let 表达式时,我们丢弃扩展后的环境——其中的绑定现在已经超出了作用域。这种环境的使用方式与作用域检查、解释器和名称解析的用法直接类似。

Exercise 练习

Complete this compiler, and test that it works on all these and any other examples you can throw at it.

完成这个编译器,并测试它在所有这些以及其他任何你能抛给它的例子中都能正常工作。

-

This makes allocating and using arrays particularly easy, as the ith element will simply be i words away from the starting address of the array.

这使得分配和使用数组变得特别容易,因为第 i 个元素将简单地距离数组的起始地址有 i 个字。 -

This is a simplification. We’ll see the fuller rules soon.

这是一种简化。我们很快会看到更完整的规则。 -

Note that we do not care at all, right now, about inefficient assembly. There are clearly a lot of wasted instructions that move a value out of

raxonly to move it right back again. We’ll consider cleaning these up in a later, more general-purpose compiler pass.

请注意,我们目前完全不在乎低效的汇编代码。显然有很多浪费的指令,它们将值从rax移出,然后又直接移回。我们将在稍后更通用的编译器阶段考虑清理这些指令。